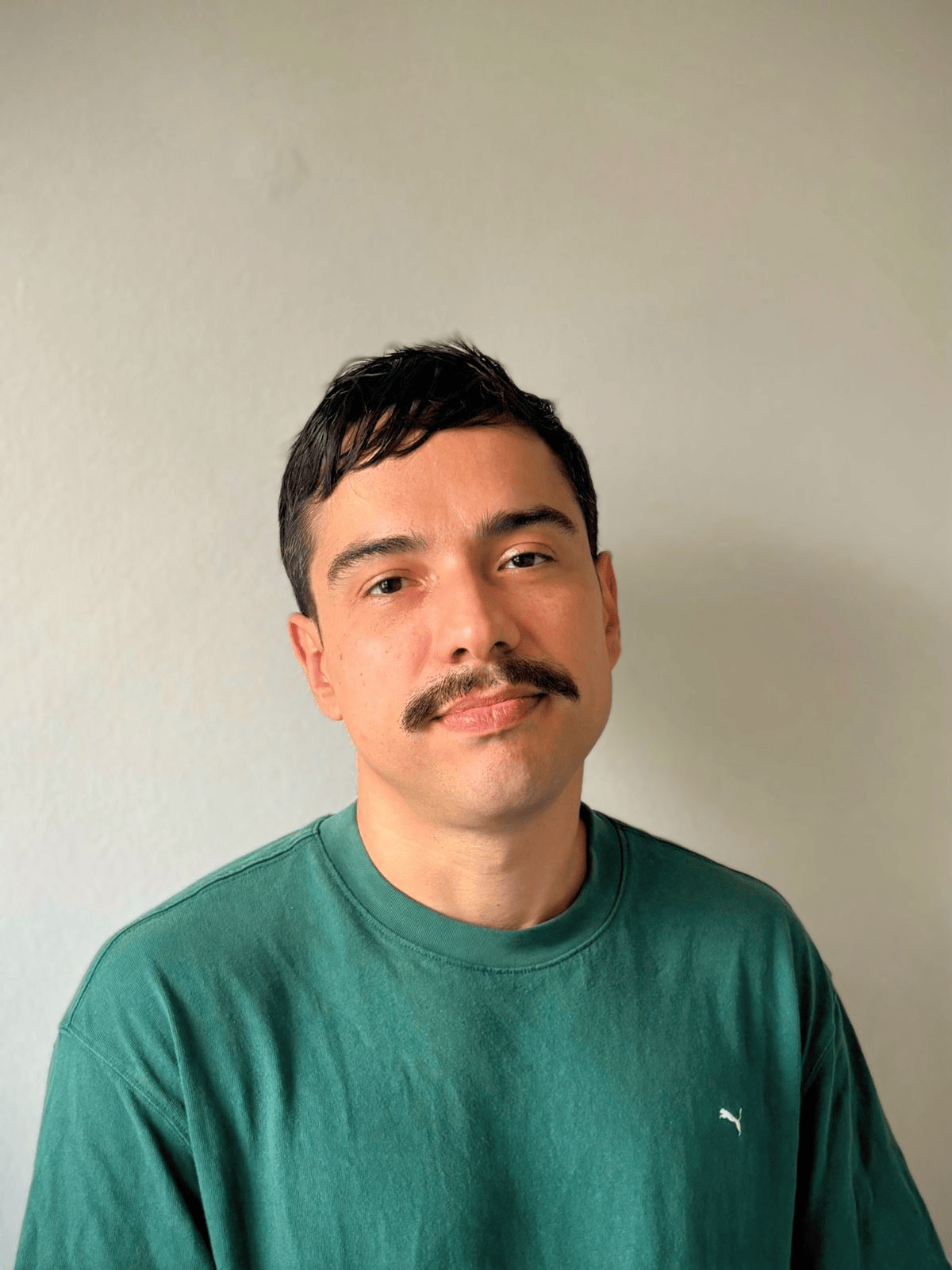

SONA presents MIKE DUTRA

CURIOSITY IN PROCESS: TEST, TRANSFORM, REPEAT

For Mike Dutra, a multidisciplinary artist based in Fortaleza (Brazil), creating is an everyday practice, about experimenting, testing, tweaking things just to see what happens. Every sound or object sparks curiosity: a different timbre, a click, a noise that keeps repeating. There’s no grand project or search for results, only the process itself, trial and error, observation, modification, and the desire to understand what sound can do.

His first direct contact with music happened at school, watching local bands play at small events. What began as curiosity soon became an obsession. Music wasn’t something that surrounded him at home. His parents had no connection to instruments or musical training. The impulse came from outside: first through the guitar, then through Brazilian rock, and later through something that would mark his path profoundly: punk.

Punk brought with it a way of acting in the world, a radical ethic that combined class consciousness, anarchy, and the idea that anyone could start a band and express themselves without asking for permission. That do-it-yourself principle shaped his relationship with sound. From his teenage years into his early twenties, Mike lived that scene intensely, rehearsing, composing, performing, exchanging ideas with other bands. The urgency to create mattered more than refined technique. In punk, exclusively covering other people’s songs felt almost unthinkable; the drive was to turn one’s own restlessness into sound.

The next step was studying music at the Federal University of Ceará (Brazil), where he stayed for just over two years. The environment offered structure, established repertoires, theory, and technique, but also limits. The program favoured traditional training, focused on notation and historical repertoire, while Mike was drawn to what escaped those boundaries: noise, the raw materiality of the voice, sounds that didn’t fit the logic of musical notes.

At the university, he joined Sonoridades Múltiplas, a research group coordinated by Professor Consiglia Latorre. Since 2012, the group has offered workshops on free improvisation and open sound experimentation to students and the wider academic community. It became a space for expanded listening and experimentation, a laboratory for testing the limits of sound, gesture, and composition. That experience made him realize that his creative restlessness didn’t fit academic molds. Leaving the program was not a rupture but a continuation of the same impulse that had driven him since punk: the urge to record his own creations.

Recording, for Mike, is the gesture that drives all sonic creation. Through repeated listening, ideas take shape. Audiovisual work expanded that gesture. He recalls the impact of hearing, for the first time, a recording made with a shotgun microphone: the clarity, the depth, the texture. Until then, his recordings were made straight into a computer’s sound card, using basic Windows voice recorders, homemade, noisy, imperfect. Access to professional gear opened up both technical and creative horizons: sound became a raw material to sculpt in detail, texture, and motion.

Cinema, as he puts it, “swallowed him whole”. It brought a new perspective. In music, the basic unit is the note; in film, it’s the sound itself. Any sound. The wind’s murmur, the creak of wood, the charged silence between gestures. That discovery resonated with his punk roots, where experimentation and subversion were guiding principles. From then on, he began to think of sound as an expanded material, capable of shaping narratives and opening worlds, not just supporting melodies. At the same time, working in film offered something music didn’t: financial stability. Sound work became a livelihood that allowed him to keep experimenting without compromise.

From there, came an interest in electronics. If punk had been the first transformation, and cinema the second, electronics became the third turning point. His curiosity about how sound machines worked led him to study circuits, components, and ways to modify them. He never aimed to become an engineer, only to tinker, to adapt and create his own instruments. Guitar pedals, simple synthesizers, and homemade devices became part of his toolkit. For Mike, each object can work like an album, a body that carries its own musical ideas and intentions.

That exploration brought him closer to Fortaleza’s visual arts scene, where sound installations and electronic experiments started finding space. He exhibited works at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Ceará (MAC-CE), as part of the collective show Anunciação: vou te olhar no vazio imenso (2025), curated by Clébson Francisco. Although visual art might seem less collective than punk or cinema, showing his work in a group exhibition made him see how it too depends on exchange, on learning through collaboration and shared curiosity. Reflecting on the exhibition space also led Mike to think more about the visual dimension of his sound work. For him, when sight and hearing intersect, there’s an inevitable performative, almost theatrical tension in watching a handmade circuit emit a pulsing frequency.

Through all these phases, composition remained the core. In punk, he wrote his own songs; in film, composing means shaping the sonic narrative, giving rhythm and density to images; in electronics, it means designing how an object can alter sound perception while carrying aesthetic intention. For Mike, this expanded notion of composition ties everything together. What matters is not the final form but the process, the act of organizing sound, timbre, and texture into meaning.

Improvisation is where this approach becomes most visible. Mike often records long improvisation sessions with guitars, homemade synths, pedals, and other instruments. Later, he listens back, extracts fragments, edits, and arranges them. It’s a gradual process: adding a sound, tweaking a parameter, seeing what happens. A small detail, “a slight change in the attack of a repetitive kick”, can open another sonic world, reveal harmonics, invite new layers to emerge. Sometimes the improvisation resolves itself. What began as a draft becomes the composition. That attitude collapses the hierarchy between rehearsal and finished work, placing the process at the centre.

This way of working also shapes his relationship with cinema. In recent films, he has integrated sounds produced on his own synths. They rarely appear in the foreground, but as subtle layers that sustain the narrative. Improvisation, in this context, functions as a reservoir of possibilities. Recording becomes the main creative gesture, while editing is another form of composing. In that sense, recording is performative: not necessarily aimed at a finished product, but part of an ongoing cycle of experimentation.

That focus on process leads to a recurring question in our conversation: “When does a sound become music?”. What distinguishes raw sound from musical form? For Mike, transformation happens through repetition, through listening, through the ability to find new worlds within the same sound. The border is thin, and that unstable zone is exactly where he prefers to work. That’s where sound ceases to be just matter and becomes experience. It’s not about producing a finished work, but about placing oneself before sound as an open field, letting listening lead the way.

This conception also informs his view on the divide between “artist” and “technician”. In film, Mike directs his own works, including Não Quero Viver em Tóquio (2016), Nego Tem Que Se Virar (2018), Paisagem na Garganta (2019, with Gabi Trindade), and Preces Precipitadas de um Lugar Sagrado que Não Existe Mais (2020, with Rafael Luan), while also working on projects by other filmmakers. This dual position places him in an ambiguous territory: directing is often seen as creative, while technical work is seen as execution. For him, however, technique is also a creative act. Each project offers a different degree of freedom, and within that space there’s always room for sensitivity and invention. The difference, he says, is mostly symbolic, the technician is seen as support, the artist as author, a distinction he considers illusory.

During our recording session for SONA, Mike presented two pieces. The first, Lá vai o cara do picolé descendo a ladeira (There goes the popsicle guy down the hill), was built with two synthesizers, a sampler, and a sequencer, starting from a seemingly non-musical texture and gradually evolving into something “possibly musical”. Layers of sound are stacked, removed, and partially concealed, as if composition were a process of addition and subtraction: elements appear, occupy auditory space, retreat, return transformed. This dynamic, of building and erasing, creates tension, drawing the listener inward and challenging them to hear in layers rather than lines.

The second track is Cidade Trincheira, a song for voice and guitar that Mike had kept since his band days, never recorded before. Recording it now was a way of crystallizing a phase, giving form to something important that had remained in suspension. The lyrics, raw and direct (“with one and a half litre of gasoline / I’ll set fire to private property… Fortaleza is an entire city, a trench”), function as a poetic gesture of rupture and exposure. Images of fire, knives, and trenches convey both political and emotional urgency, a desire to break through hegemonic and oppressive structures, which is a recurring theme in punk. At the same time, the lyrics reveal a personal ambivalence (“I’m afraid of attachment and don’t take anything seriously… to jump or not?”), which resonates directly with his risk-taking approach to sound experimentation.

The brutal clarity of the lyrics in Cidade Trincheira contrasts with the electro-acoustic layering and sound displacement in his first track: while his electronic work aims to open new sonic worlds through subtle variations and timbral shifts, this acoustic guitar song asserts a lyrical stance, a voice laid bare without mediation. Recording it now meant embracing that tension, between performative risk and the vulnerability of the voice, and demonstrating that, for Mike, experimentation involves taking narrative and emotional risks, not just technical ones.

Mike Dutra’s trajectory shows how creation can cross different fields without losing a central core. From punk to electronics, from cinema to sound installations, everything is driven by the same obsession: recording, composing, improvising, experimenting. The smallest detail that opens up another world, the act of soldering a circuit, the decision to cut a segment of improvisation and turn it into a composition: all of these are ways of living art as a process, rather than as a product.